Pat and Selwyn Jones can boast something rare for a commercial vintner: they have quite possibly met every single person who has ever bought a bottle of their wine. In spite of requests from restaurants, and the convenience that retail sales would offer, they choose to sell their product in person at farmers’ markets and local events like the Denman Island Christmas Craft Fair, so they can ensure that all their clients know where their wine comes from and how best to store and serve it.

This dedication to authenticity, quality and personal connection is what draws people to the Denman Craft Fair year after year, says Craft Fair Coordinator, Autumn White. “I’m excited that Pat and Selwyn, of Corlan Vineyards, will be selling their wines at the fair again this year – they’ve been a big hit since they started vending at the fair two years ago. Their wine exemplifies the Craft Fair’s values of small-scale, hand-made, local and sustainable.”

As well, this year the Jones will also take part in the event’s food fair, offering comfort food such as home-made soup and shepherd’s pie, all based on products from their farm.

The personal touch is important for Corlan’s wines, says Selwyn, because the wines do not contain potassium metabisulphite, a preservative used in most commercial wine, including many organic wines. This reflects the Jones’ commitment to purity.

“We want our wines to be completely natural,” says Pat. Some people have allergies to sulphites, or find them hard to digest, and many people simply prefer to avoid preservatives in food and drink.

However, without sulphites, wine needs to be drank within three days of opening to ensure quality. After that, it begins to oxidize, compromising its flavour.

“It’s best to open our wine when you have friends over,” says Selwyn. “We need to be able to explain this to our customers, so we need to have face-to-face sales. It’s also important to explain that the shelf life of the wine, if unopened, is great. It just gets better and better.”

Corlan produces four wines, sold under the label To Ewe Wines: Sandy Island White is made with Corlan’s estate grown Ortega, a cross between Muller-Thurgau and Seigerrebe, which produce a crisp aromatic wine with citrus overtones. Siegerrebe is another aromatic white which is a personal favourite of the winemakers.

Chrome Island Red features Marechal Foch grapes, a French-American hybrid which ripens dependably in our climate, and produces an inky red, which is aged in neutral barrels.

Blackberry dessert wine is Corlan’s only sweet wine, and a favourite on Denman Island, where blackberries grow abundantly.

“Our wines have a strong fruit flavour,” explains Pat. “This is because we don’t irrigate the vineyards. This also means we’re not depleting the groundwater, which is important for sustainability. There are parts of Europe where this is practiced. It gives the wine more flavour.”

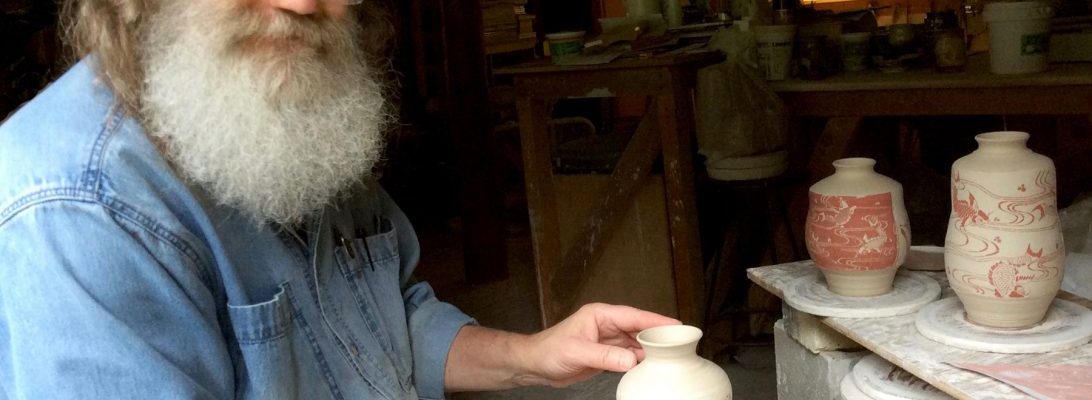

Corlan is Denman Island’s only vineyard and winery. All the wines come from fruit (mostly Ortega and Marechal Foch grapes, and blackberries) grown on the sunny 10- acre certified organic farm, which also includes Clun Forest Sheep, three working border collies, a large flock of laying hens, a propagating greenhouse with nursery, and a tasting room.

Running a certified organic farm is labour intensive but the Joneses wouldn’t have it any other way. They love the work itself, the long days in the garden and vineyard, and the payoffs. “It gives you a tremendous feeling of independence. We produce most of our own food. We’re almost completely self-sufficient. And the biggest blessing is that we know what we are eating. We know it is chemical-free and healthy,” says Selwyn. Weekends find them at the Denman Farmers’ Market and the Qualicum Farmers’ Market, making those face-to-face sales. They are looking forward to the Denman Craft Fair, partly because it’s a magical and fun community event, but also because the sales are brisk.

“The Fair is great for us,” says Pat. “We get people coming back each year. Wine makes a great gift.”

Busy though they are during the Fair, Pat and Selwyn also find time to do their holiday shopping on site. “It’s such an easy, nice place to buy presents, without having to go into stores at this time of year,” says Pat. Just like their clients, they love the face-to- face exchange of hand-made, high-quality, sustainable products.

Originally published in The Island Word, November 2017 photos by Colby Rex O’Neill

You must be logged in to post a comment.